|

|

Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less.

- Marie Curie

We are hearing more and more from experts about how climate change is going to determine the near-future of everything. What's the basis of these statements? Some questions you might have are:

- What are the main drivers of climate change that inform such projections?

- What are and when will be the effects in a business-as-usual projection?

- What action can we take that is meaningful, accessible, and effective?

Here's a 2-part online seminar I gave to the ClimateMatch Community on how to think about the Energy Transition narrative path we are pursuing:

If you prefer text, the following text provides similarish content as an ongoing synthesis. There are two sections:

- Salient features of this complex problem

- Common positions taken in response to the climate emergency

There's a standard TL;DR Summary on the state of the climate emergency.

- Scott Denning's is "Simple, serious, solvable".

- Grace Lindsay's is "It’s happening. It’s us. We can fix it.".

- Another popular version: "It’s real. It’s us. It’s bad. We’re sure. There’s hope."

- The physics of the problem is simple: an Earth Energy Imbalance.

The earth absorbs light energy from the sun and re-emits energy as heat back into space. A fraction of this heat is trapped on earth by greenhouse gases (GHGs). How much fluctuates year by year, but there is an upward trend of 0.87 +/- 0.12 joule/second/meter2 (2010-2018 average; this year's value is 1.64). This is alot! It's an energy rate equivalent to 300 Hiroshima bombs hitting Earth every minute. Given a blast area of approx. 8 km2 for one, that would cover all land on Earth every 6 months. Most of this heat is actually absorbed by the oceans, but that capacity isn't limitless, is having its own cascading sequence of negative effects, and the relatively small remainder that gets absorbed and held by the land and atmosphere is still large enough to present an existential problem for us. We need to lower the GHG concentration in the atmosphere so more heat can escape. Instead, we are increasing GHG concentration by burning fossil fuels, which traps more heat, accumulating year over year. - It's worse than you think.

The underlying physical and socio-political mechanisms at play in climate change make the worst case projections both more probable and worse than you might have expected. Moreover, the year-to-year adjustments in projected timelines for salient adverse climate effects keeps moving them closer. Tending to be situated in more affected regions and with less means to protect themselves, more and more poor countries are seeing the effects of climate change. This a global problem, however, and changes to everyday life are already here (e.g. extreme weather driving political instability, supply chain issues, etc.). These are projected to become more frequent over the next decades. Things can get much worse though. The high uncertainty and tail risk in what happens after 2050 merits considering worst-case scenarios. In our current business-as-usual trajectory the effects could compound into what will mark the beginning of the end of our civilization as we know it (e.g. conflict-causing mass migration and food/water shortages from regions made uninhabitable/infertile, irreparable dysregulation of the global economy, etc.). In that case, civilization would come out of this century much diminished. The effective action for us to take now is within initiatives that prop-up our civilization's resilience against collapse. - We have credible paths forward that avoid collapse. They demand system change, the seeds of which are being sown now.

After half a century of not having major impact, the vibrant science and societal movement to thread the needle to a sustainable future is burgeoning and now seems poised to make real headway. The work of this movement exudes for me a vision and resolve that is characteristic of the best of the human spirit. It gives me hope that preventing collapse is a realistic goal. Make no mistake, the stakes are everything and the hard work is ahead of us. We are fighting against the wickedest of problems: the imposing cynicism of autocratic petrostates, the distracted governance of emerging populism, and the soothing, but deluded doctrine of continual growth through tech innovation. Nevertheless, better understanding this complex arena allows us to form and execute better shots at success (even language matters). In the spirit of Marie Curie, I feel empowered by this idea to act out of my comfort zone and maybe you can be too. The alternative of staying complacent makes us complicit in the current inertia slated to destroy most everything of permanence any of us ever cared about. Let's embrace the discomfort, and channel it into speaking up and taking bold action.

Below is a list I've compiled of what to me seem like important features/impacts of the climate emergency, organized by sector.

A pedagogical, slides-based video lecture with even more detailed content (filled with eye-catching graphs!) is linked to below.

Disclaimer: While I've aimed to be thorough, any such list is surely incomplete and subjective! I'm happy to take suggestions for additional content.

Climate:

- It is important to remember that net-zero CO2 and the eventual reduced atmospheric temperature is an important target, but not the whole story. The fundamental symptom of the crisis is the Earth Energy Imbalance (EEI). There are other greenhouse gases other than CO2 (like methane) and there are consequences to climate other than atmospheric temperature (like ocean warming) that we also need to keep in mind. Temperature changes can also have large effects on how bodies absorb or give off GHGs (e.g. there are large and consequential uncertainties in when land-based carbon sinks will saturate and how they'll respond as we lower our GHG emissions).

- While the convention is to track climate change with average temperature increase, weather variability is also growing in most locations and is the largest source of risk to us. For example, heatwaves, even short ones if strong, can have lasting effects on the human population and the crops that sustain it (extreme events driven by Rossby waves is an example).

- Strongest effects are heterogeneously distributed over the planet and capacity to adapt in the near-term at a given location depends on socio-economic status. For example, without access to air conditioners and electric power, the largest threat of heat to human health is combined high temperature and humidity ('wet-bulb temperature').

- The massive scale of climate change means that for any given direct effect there are typically many indirect and/or early-onset effects. Take sea level rise. It directly affects coastal areas. One indirect effect on everyone is the disruption of coastal infrastructure that supports world trade. Another is the forced migration of half a billion people inland, stressing inland resources. Another is rising the ground water level, which can damage underground infrastructure (e.g. gas lines) deep inland.

- In many cases, the change in official projections year by year continue to be in the worsening direction. The IPCC report only started discussing tipping points in earnest last year, of which many seem to be approaching faster than anticipated.

- CO2 emissions have been coupled with aerosol emissions, which have masked and delayed the full warming and precipitation effects. Temperatures are likely to rise more quickly in the coming years as we emit less aerosols (a good thing for our health!). Let's not get frazzled by this and instead prepare adaptation measures now.

- Neo-classical economic analyses systematically underestimate climate risk so take those projections as best-case. Even in contemporary work, the value placed on precision biases the focus onto what can be or has been measured to high precision, which often excludes determining factors, ultimately limiting the research program's predictive power. Better handling of uncertainty in this research will allow for including more determining factors.

- While it deserves constant scrutiny, there is an earnest movement among a significant portion of the financial industry regulators who see the value that will be lost in a business-as-usual projection. They, e.g. GFANZ, are mostly on board with making big changes such as funding the transition ($130 trillion so far) and accepting that large assets will be stranded in the process. Standards are emerging: climate-related financial disclosures is one; Net-Zero Standard is another.

- The goal is for a so-called orderly transition off fossil fuels along which companies have the opportunity to plan. This is contrasted with a disorderly transition characterized by frequent, unanticipated shocks that disrupt the economy.

- The transition to renewable energy is projected to cost on the order of other great infrastructure projects of the past, with similar spillover benefits to all areas of the economy (e.g. indoor plumbing).

- While a price on pollution is unpopular (even with rebates!), experts say it's the best economic device we have.

- New kinds of financial instruments are being developed to facilitate internalizing the costs of pollution. Instead of sticks, carrot (i.e. positive reward)-based policy is under development, e.g. a carbon coin/currency and carbon border adjustments for handling heterogeneous implementation across countries.

- The fossil fuel industry lobby has, however, been effective at protecting their intention to continue production into the next decades. E.g. the Inflation Reduction Act, celebrated as cementing development of the renewable energy sector, also supports continued development of the fossil fuel industry.

- The transition will not happen through market forces. Renewables are cheap, but investment follows profit, not price, and in the absence of stronger regulation, fossil fuels make investors too much money.

- The degree to which economic growth can be decoupled from physical resources is a complex, ideology-laden debate (the two sides even differ in what decoupling means) that nevertheless seems to have an empirical resolution: there are lots of examples of partial decoupling (e.g. within the economies of specific nations, even when exported emissions are included), but the kind of global decoupling that would make current rates of growth consistent with a sustainable future seems unlikely.

- Cheap oil is waning and energy sources are diversifying. The latter aren't as energy-dense or versatile as oil though, so expect economic contraction globally, because the viability of many business models and lifestyles depend on cheap energy and a low cost of carbon. This economic contraction will likely adversely impact our efforts to further develop and deploy renewable energy.

- New technologies must scale well to be useful solutions (e.g. sourced material for any physical product must be plentiful, cheap to source, and affordable on a global scale). Very few do. Moreover, efficiency claims should be based on the entire manufacturing and product life cycle process, not just what the technology delivers.

- Tech solutionism can skew rational evaluation of new ideas. The start-up model hasn't proved itself yet in these large-scale, poorly grounded coordination problems, and "moving fast and breaking things" is a philosophy that actively generates and ignores externalities, which is largely what got us here.

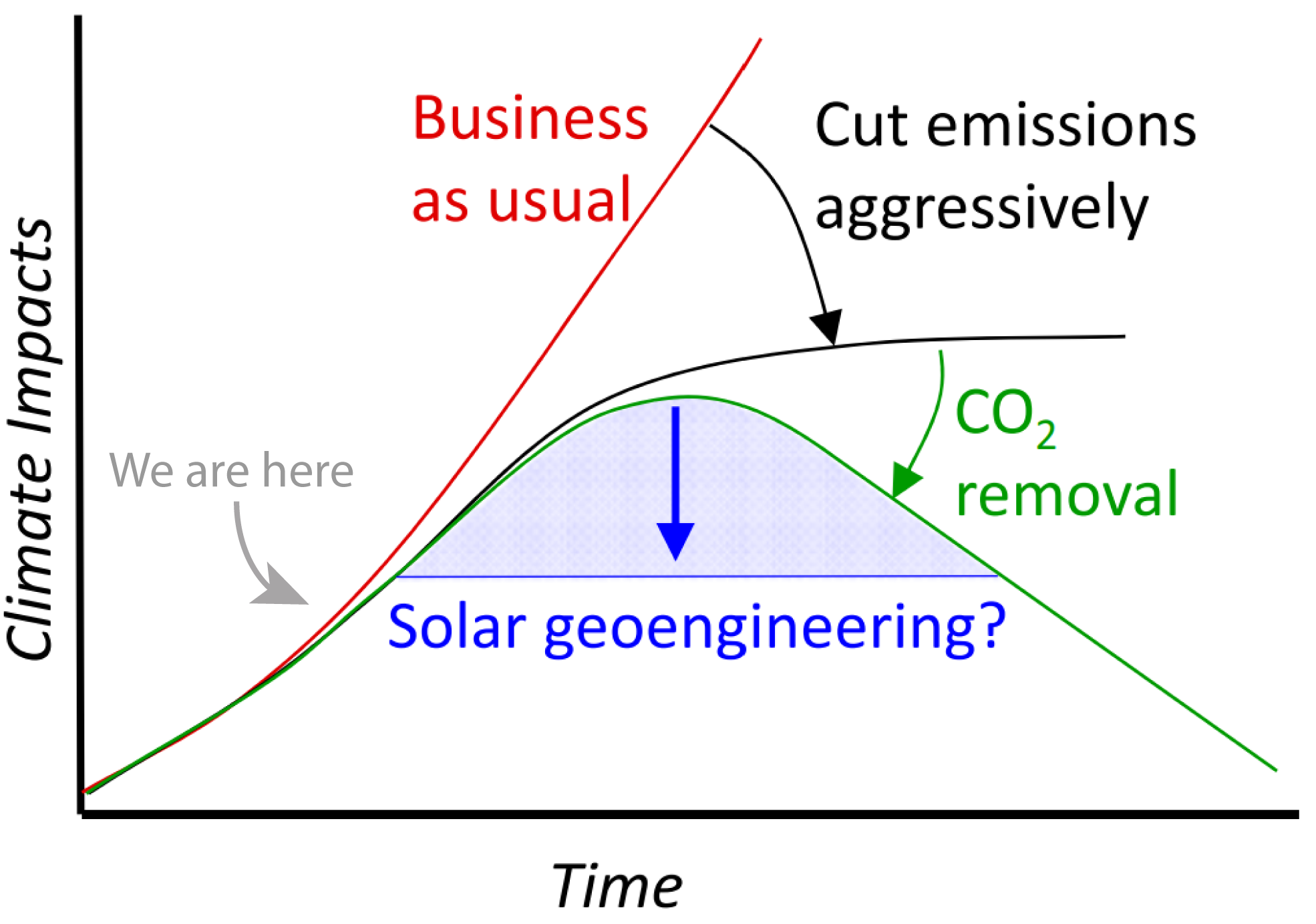

- Geo-engineering to pull CO2 out of the atmosphere will likely be necessary. Geo-engineering to reflect sunlight away in the meantime will also be needed (See the schematic below from MacMartin & Kravitz PNAS (2018)). We are still developing our understanding (e.g. peer-reviewed proposals for stratospheric aerosol injection now seem too risky). We need a Manhattan project for geo-engineering and, when deemed necessary, start with the safest, accessible approaches.

- Our current global energy consumption rate of 17 terawatts (17 x 1012 watts!) is supported mostly by burning fossil fuels. The bulk of this consumption, and thus of fossil fuel emissions, is concentrated in affluent countries and affluent individuals (through both lifestyle and financial investments). Despite large increases in efficiency over the last 50 years, per-capita energy consumption has not declined but leveled off since the 1970s. With our population slated to grow by a few more billion over the rest of the century (though it's up for debate if this can be realized due to climate change), the additional energy required to satisfy that per-capita rate is more than all currently produced renewable energy.

- Era of cheap oil is coming to an end. Peak production is in a decade or so, followed by gradual decline.

- Comprehensive projections that keep temperatures within 2 degrees negate new fossil fuel developments.

- There's consensus coal needs to be phased out but large and increasing consumption in India and China is offsetting coal reductions elsewhere.

- Standardized emission calculations center around 3 scopes: upstream emissions from material inputs (scope 1), processing emissions during manufacturing (scope 2), and downstream emissions from using the output product (scope 3). For the energy sector, scope 1 and 2 emissions are large, but are still dwarfed by massive scope 3 emissions - the processed fossil fuel itself. The latter are not in official discussions on regulating the emissions of the fossil fuel industry, though there are calls to include them. In practice, this means regulating production, a move for which governments currently lack a mandate. As climate change worsens, however, and society more actively confronts Big Oil, passing production-limiting regulation will likely become a fierce battleground.

- The fossil fuel industry has proposed scope 4 emissions (those avoided by emission-producing activities), but the concept has been rejected by regulatory bodies and has no validity within official emission accounting.

- There are lots of means for the sector to evade emissions reduction. For example, as dirty assets become a liability, there will always buyers and this off-loading presents problems for tracking and transparency.

- The zeitgeist around a transition to net-zero means Big Oil has to talk transition to please investors. However, this doesn't imply they are actually taking substantive action.

- Given the track record, it's mostly domestic lobbying and economic interests that shape the climate policies that political leaders campaign on and push for.

- Domestic climate politics is increasingly partisan with support for climate policies such as carbon pricing divided along ideological lines.

- Fossil-fuel producing nations are increasingly autocratic/oligarchic and kleptocratic. They will exert control over pricing via rates of production to slow-burn the extraction of as much of their remaining reserves as possible to maximize their profits. To avert civilizational collapse, most of these reserves need to stay in the ground. These actors are thus perhaps the largest impediment to mitigating climate change. The emerging alliance between Russia and Saudi Arabia is a timely example of large producers/emitters that will be hard for the international community to compel to leave reserves in the ground.

- Increased resource scarcity will embolden and empower aggressor states that will put increasing pressure on world order and peace.

- As our institutions become more pliable in response to the calls for change, all actors will try to manipulate the change process to their advantage. We need increased institutional strength and agility, not reduced institutional oversight.

- As we saw with the pandemic response, a good solution can fail to be implemented effectively. We need to translate the vision and commitment we currently have at the global scale back down to the scales of nations and peoples.

- Collectively, we are uninformed. In the developed world, we think climate change is an issue address through personal choices not system change.

- Concern about climate change and even knowledge about it isn't a great predictor of what changes we are willing to accept.

- We seem to want an effective and fair transition, for others and for ourselves.

- We are more swayed by explanations of how proposed policies do this rather than by explanations of the climate impacts these policies aim to mitigate. We are also swayed our culpability, when communicated clearly.

- Feelings and values influence our decision-making and will affect how we evaluate explanations of outcomes.

- Existential risk organizations don't always place climate change at the top. Despite a focus of AI alignment/safety research on existential risk, it is unclear if the research and tech infrastructure needed to develop advanced AI (even on near-term timelines) can exist in a business-as-usual projection. A more pressing concern is the negative impact that existing AI (e.g. recommender systems) is having now on public discourse and democracy via active and passive curation of public opinion.

- A mass extinction event was already underway independent of climate change due to human activities like habitat destruction.

- Climate change accelerates and exacerbates this trend, with an estimated half of all species going extinct by 2050.

- Two stark examples: (1) the Arctic marine ecosystem may be completely destroyed by the loss of sea ice (on the underside of which is the algae forming the bottom of its food chain), and (2) the southwest of the Amazon rain forest will likely transition to savannah by 2050.

- The biosphere's resilience is collective, so it is an important goal to do what is possible to conserve remaining species and habitats.

Degrowthers: Reduce consumption and preserve the natural world that sustains us.

- Pro: This is the right goal. A sustainability-oriented society is where we need to end up.

- Con: It is unclear how to overcome high initial social & structural barriers.

- Pro: Markets (for capitalists) and emancipated Labour (for socialists) are powerful forces for technological innovation.

- Con: It is unclear how to globally decouple this growth from further degradation of the environment on which we depend.

- Pro: Counter-intuitively, they provide an activating psychology that empowers in face of climate emergency.

- Con: Near-total societal collapse is often baked in as an axiom. That's unjustified and distracting given current uncertainties.

- Others are doing their own process (e.g. JTOlio, Grace Lindsay), and coming to similar conclusions.

- There are great communicators out there to follow. Two I find balanced, thoughtful and well-informed are Genevieve Guenther and Ryan Katz-Rosene.

- I recommend reading Ministry for the Future (free pdf), an excellently researched, utopian speculative fiction novel that takes the dire situation we are in now and projects how we might make it better over the next 30 years. A more granular, character-driven novel of the American experience over the same timespace is Deluge by Stephen Markley.

- Inspiring initiatives that can be scaled up immediately with low risk: